Around the time of the industrial revolution young children were cared for by their parents, godparents, family servants, apprentices and neighbours. Barbara Hanawalt (author of Growing Up in Medieval London) makes the point that 'child care in London may not have been organised, but the streets and houses were crowded with adults going about their business or pleasure.'

Women and children working in the cotton mills, 1820.

View of crowded Ancoats c 1870s, England.

It was not until Edwin Chadwick and Friedrich Engels brought about awareness into the "appalling plight of the poor," that childcare legislation came about throughout Europe and America.

Key thinkers of educational thought

In the 18th century, towards the end of the Enlightenment, Jean-Jacques Rousseau(1712-78) and Marc-Antoine Laugier (1713-69) believed in the notion of the restoration of man's natural being and habitat.

Rousseau in the 1750's portrayed the primitive savage as a natural man; a noble and magnificent creature on a higher and more natural plane of being than contemporary man, whilst Laugier who believed in an absolute, 'essential' beauty to be found in Nature depicted the primitive hut (made of a lightweight construction of trees and branches) as the origin of all possible forms of architecture.

Frontispiece of Marc-Antoine Laugier: Essai sur l'Architecture 2nd ed. 1755 by Charles Eisen (1720-1778). Allegorical engraving of the Vitruvian primitive hut.

A belief in nature and the restoration of natural man - Rousseau rejected the city in favour of a decentralised rural utopia, whilst Laugier shared his belief in the picturesque value of landscaped gardens and parks was more pragmatic, showing how cities could adopt wider roads and avenues of trees and parks.

Frontispiece to ''Emile'', by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau wrote Emile (or 'On Education) in 1762 and was highly influential on early educational ideas. The fusion of its ideas, combined with radical scientific thought, led to a new perception of childhood, teaching methods and the aim and purpose of the educational process.

From Stewart and McCann, The Educational Innovators:

"...It's originality lay in the fact that it was the first comprehensive attempt to describe a system of education according to nature. The key idea of the book was the possibility of preserving the original perfect nature of the child by means of careful control of his education and environment, based upon an analysis of the different physical changes through which he passed from birth to maturity."

Rousseau's ideas were so radical they were the philosophical basis for the key pedagogical pioneers - Pestalozzi, Owen, Froebel and Piaget.

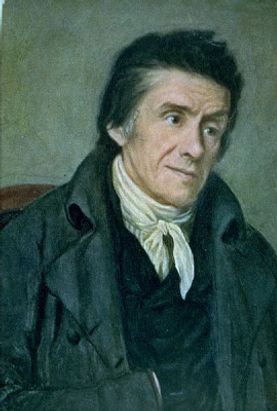

Pestalozzi

Johann Henreich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) was inspired by Rousseau and Naturphilosophie, and spent many years writing about education and teaching. He believed (like Rousseau) that education should be in complete harmony with the child, yet disagreed with Rousseau of the education of the child in isolation and, and included stimuli such as drawing, writing and talking - 'The means of making clear all knowledge gained by sense impressions comes from number, form and language.'

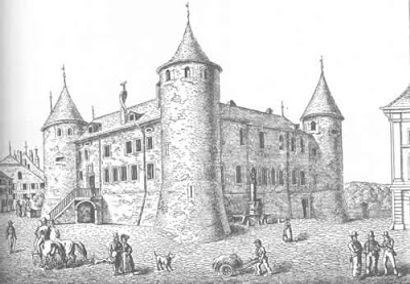

The castle of Yverdon at 1830.

In 1800, Pestalozzi opened his first educational institute, which was later moved to the castle of Yverdon in 1805, it was adapted slightly to his needs and given rent-free. Furnished simply, it had many spacious halls, a large courtyard, a meadow and broad avenues which were to serve as playgrounds.

Yverdon became very influential, with numbers growing to over 250 pupils, who came from all over Europe, Russia and America. However, it did not cater specifically for very young children.

Owen

Robert Owen (1771-1858), a Scottish mill owner visited Yverdon in 1818 and opened the first infant school in Britain at his New Lanark cotton mills.

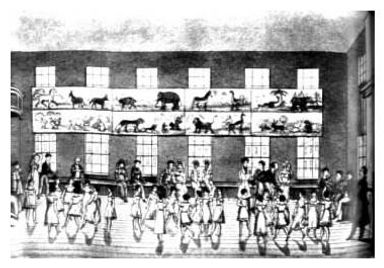

Interior perspective of the New Institution for the Formation of Character, New Lanark.

North-east elevation and plan of the New Institution for the Formation of Character, New Lanark.

Owen viewed education as an instrument for social change. Books were excluded and activities such as singing, dancing, marching and basic geography took their place and the children spent three hours a day of free play in an open playground. The school was part of Owen's model factory settlement which included apartments, a canteen, a recreational facility and the evening institute. Architecturally the school building was similar in style to the rest of the factory settlement, of late Georgian industrial form. Owen's system differed slightly to the Pestalozzian philosophy with the absence of arts and crafts activities, the emphasis on the physical rather the intellectual and emotional development of the child.

Froebel

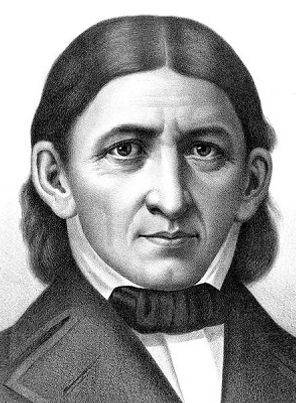

The most influential educational theorist during the second half of the 20th century was Frederich Froebel (1782-1852). Froebel was interested in nature during his youth and undertook an apprenticeship in forestry, before going on to study biology and mathematics. It was when he was invited to study at a school in Frankfurt that he adopted Pestalozzi's revolutionary methods and found his true vocation. From 1807 to 1810 he worked under Pestalozzi at Yverdon where he recognised the importance of creative development through play as opposed to discipline. He believed that children had a unique understanding of the innate truths of life, and this could be reawakened by playing games that had symbolic meaning. For him, the kindergarten should reflect an ideal society - 'children's garden' referred to the total environment for the child: the garden and building representative of the natural world. This was important because his theory was that children understand through symbolic language which utilised metaphor and analogy. He created "gifts" to teach children and 'encourage them to carry out various sorts of creative and expressive handiwork, where self-activity became the means of education.'

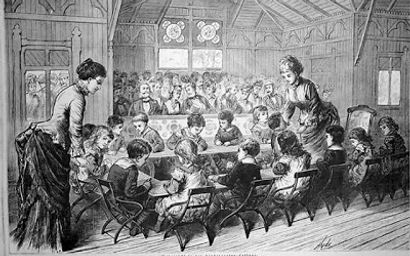

Artists impression of a Froebel Kindergarten showing at The Centennial World Fair in America. The children are playing with the Froebel 'gifts' at the table.

Froebel's 'Kindergarten' influence was vast, with kindergartens being established in Australia, Canada, India, Austria, Japan, Russia, Turkey, France, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and New Zealand.

Montessori

Maria Montessori (1870-1952), in 1896 was the first woman to graduate in medicine in Italy. She then worked in a psychiatric clinic at the university specialising in the treatment of retarded children and studied the methods of Jean Itard and Edouard Seguin in Paris. Her success there led her to an interest in general education, where she then returned to university to study experimental psychology and anthropological pedagogy. She was appointed Professor of Anthropology in 1904.

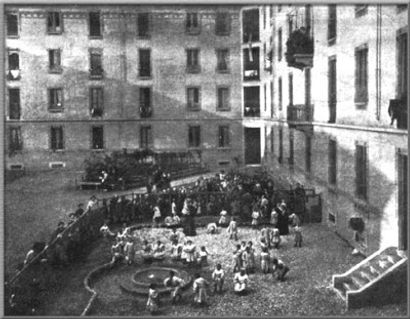

In 1907, Montessori launched Case dei Bambini, which was to care for children whilst their close-by tenements were being upgraded. Because of her success with retardedchildren, she believed that her methods would be even more effective if used in the training of normal children.

The sense of touch was an intrinsic factor in her approach to preschool education, as she believed if it was not developed now, sensitivity later could be lost. Montessori recognised three types of activity: the exercises of practical life; the exercises of sensory training; and the didactic exercises.

The first stage is freedom - to be able to perform ordinary tasks by oneself - cleaning, dressing, all furniture was at the height and scale of the children. There are no fixed desks, tables and chairs and all are light and able to be moved. Montessori designed a specific set of gymnastics exercises to develop coordination. Similar to Froebel's Gifts, the didactic apparatus of Montessori combines physical co-ordination with natural thought development.

For 40 years Montessori travelled throughout Europe, India and the USA giving lectures and papers and establishing teacher training courses.

Pestalozzi and his school of freedom, Froebel's kindergarten, Seguin's and Itard's methods for educating the retarded - all were synthesised in Maria Montessori's educational practice. Today, there are still many Montessori schools all over the world for its philosophy as a humanistic and rational approach with a focus on the environment.

Steiner

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), was a theorist and sculptor of the early 20th-century expressionist period. Steiner, like Froebel before him, believed that preschool children needed to play rather than engage in formal education tasks, in order that all their spiritual, intellectual and physical powers could emerge unimpeded. However, he added that this awakening should happen with the natural world. Steiner went further than Froebel in evolving an architectural theory which set out to be in tune with the psychological needs of early childhood. He instigated a synthesis between architecture and the early childhood education and remains the clearest manifestation of pedagogic theory and architectural convergence.

Steiner, from a young age was interested in geometric forms, which he believed were 'perceived only within oneself, entirely without impression upon the external senses.' He was interested in the reconciliation of the material and spiritual and aimed to create spaces that combined both, harmonizing with the innermost subconscious senses of the mind to create 'therapeutic environments'.

Steiner studied natural history, mathematics, chemistry and philosophy and after, became a tutor. One of the four boys, was ten year old Otto who suffered from hydrocephalus and was believed to be uneducable. However, Steiner quickly identified the symbiotic relationship between bodily functions and spiritual well-being, and sought to liberate Otto through gentle encouragement and the gradual stimulation his senses. The boy achieved gymnasium entrance standard in two years and eventually became a doctor of medicine.

Later, this experience helped Steiner to formulate a new education. By the end of the century he had studied the work of Kant, Fichte, Herbart, and Nietzche, Marx and Engels and later Breuer and Freud. He also became aware of the theories of Hume and Darwin, and Einstein's work on relativity. Through this academic emersion he developed his basic philosophy (anthroposophy), 'the wisdom of man combined with his spiritual being'.

In 1900 Steiner became interested in the newly emerged theosophy, and in 1907 arranged an international theosophical congress in Munich. Here, music, recitation and drama were linked in a dynamic interaction appealing to all the senses.

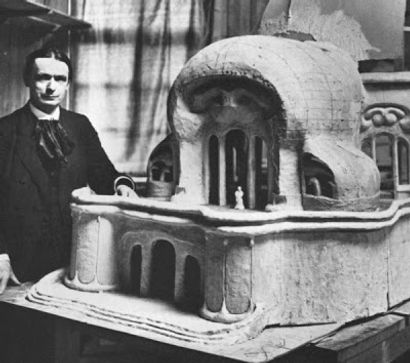

Steiner standing with his model of the first Goetheanum building he designed.

In 1912 the first Anthroposophical Society was formed, and Steiner designed the first Goetheanum to house the Anthroposophical Society. Many artists and craftsmen worked together on the building. Steiner showed how 'vitality of form could be achieved, how a concave surface leads into a convex one, creating a living, curving surface.

Later, Steiner's architecture influence was applied exclusively to kindergarten design, an expressionism that Kenneth Bayes described as having three characteristics: movement (particularly of line), sculptural form and metamorphosis of form.

Duldeck Haus Dornach, Switzerland, by Steiner, 1915-16.

These ideas were demonstrated at Dornach, which became an ideal Steiner community where a number of organic buildings were constructed, including the Duldeck house above. His architecture has a sculptural quality, a plastic, moulded appearance that resembles distorted crystalline shapes. Kenneth Bayes suggests that it originated in Goethe's analysis of the plant 'as an earthly image of a spiritual archetype. Budding and sprouting the archetype being of the plant embodies itself through successive metamorphoses of form until it reaches its full expression'. Steiner's idea was that one inorganic form would be added in sequence to another to create a system which resembled an image of growth - incomplete (and therefore dynamic), and natural.

In summary

Much is written on the subject of education, but very little deals with the architecture. In Britain, early childhood facilities are merely add-on's to existing classrooms or conversions of existing buildings with no real concern for the needs of the child.

All notes are taken from this book: 'Kindergarten Architecture' by Mark Dudeck.